What is warmth?

Hobart, September 2019

Writing from the fickleness of Tasmania’s spring, I’m remembering – and missing – Irish weather. Today it’s raining; snow is once more predicted for the mountains; and if the sun delivers I’ll be diving for shade or a sun hat.

I’m attempting to nurture my solastalgia: a preoccupying melancholy about the warming planet, and our future so characterised last week when students, led by the remarkable Swedish sixteen-year-old Greta Thunberg, mobilised to implore adults to wake up and DO SOMETHING about climate change. The rally in Hobart was vibrant with adolescent energy, leaping dogs, and activated adults flocking into the madding crowd. The bitter sexist comments directed at Greta in the days that followed – after her declamatory speech to the UN Climate Action meeting – flared my melancholy into anger and deep despair. Hope dies hard in these times but I’m understanding that it’s as necessary as a beating heart to staying alive.

And so I garden, ripping colonising hybrid stems from the passionfruit vine and dosing my lemon tree with chicken shit. I’ve netted the kale seedlings to keep away the blackbirds, and renovated the worm farm to encourage worms up into a new tray. In a few weeks I’ll be siphoning castings onto my tomato plants.

I listen to the report of forest fires in Indonesia: the long-term health impacts of smoke from the peat fires and greenhouse damage from spume. Peat, when left damp, is a significant carbon bank; it burns because it’s been drained to allow for plantations which have very low carbon sequestration. And when peat burns it can burn for a very long time, deep into the earth. I think of the Irish bogs – the source of fuel for home-fires and areas devoid of trees – and arrest my thoughts of the potential for all those bogs to burn if they dry out.

Stewardship.

Post home...

Boston, July 2019

Ireland to America. State-to-States. What kind of a state am I in, in Boston’s heat and crush after Ireland’s fresh winds and rural-quiet? Adjusting: in mind and body, alert to change, glad of familiar signifiers and the hospitality of family; joining the known with the unknown.

After two scorching weeks in the US there has been rain, a tornado along the east coast – that ripped roofs from buildings at Cape Cod, a favourite holiday destination for Bostonians – and a welcome drop in temperature. But, politics is burning up, following Robert Mueller’s report – on the Russian interference in the 2016 election – to the Judiciary committee, which I watched on TV for 3 hours. He was inscrutable and restrained under fire from Republicans attempting to demolish his defence and Democrats moving to sure up his case for the President’s lying about collusion with Russians.

A few weeks before ‘entering’ the States I visited Belfast during preparations for ‘the 12th’, the day in July when the ghost of William of Orange returns and Northern Ireland is again – at least more visibly – snapped in two. Unionist and Protestant iconography proliferate in designated suburbs and towns to commemorate The Battle of the Boyne of 1691: Orange bunting, the Union flag (Union Jack), the Ulster flag bearing the cross of St George and the red hand of Ulster, banners across streets – ‘safe home brethren’ – and marching pipe bands.

The blood seemed to boil over into every cell of my imagination, so that I was relieved to return to Donegal, and then to the bustle of Boston and finally to home in slow Tasmania.

Make America grate again

The Jacks proliferate

Belfast suburbs before the 12th: a bonfire being erected.

Ireland in Summer

Wind blusters in from the Atlantic to Donegal. Rain whispers in corners when not beating at windows. The sun’s appearance is a vestige, of a possible life. The woman in a shop yesterday remarked that “we had such a wonderful summer last year, the best I can remember. We can’t possibly have another!”

I evacuated Hobart’s late autumn, the ground near my house russet with maple leaves, darkening days pulling me towards imminent hibernation. And now: another dance altogether. The temperature is familiar, cool, but the light – and its closeted sunlight – feels like endless day. There’s a sense of contrariness about being alive here while remembering there.

The road to Horn Head almost does me in: my body resists the experience with a familiar tremor I can’t stem. The narrow road rises too quickly to brim across cliffs and steep grass verges rolling into the sea. I step out of the car to take photographs and the stiff wind knocks me off balance. I’m relieved to return to lower roads and a more flattened sympathetic nervous system but my tourist-self can chorus that I’ve seen the cliffs of Horn Head. Friends tell a story of a 50-point turn on an icy surface on that road while passengers shivered outside, too nervous to be in the car at the edge, above the drop. Irish mountain roads, especially when they loom as a surprise, are not for the weak-kneed.

Last week I returned to the Burren. The mauve uplands are sketched with lush green now, such a contrast to the saffron of autumn when I was here in 2018. The college is bursting with students from the US, on intensive art courses. I meet familiar staff and students from my residencies and feel gratitude for the times there and for the energy suffused into my creativity.

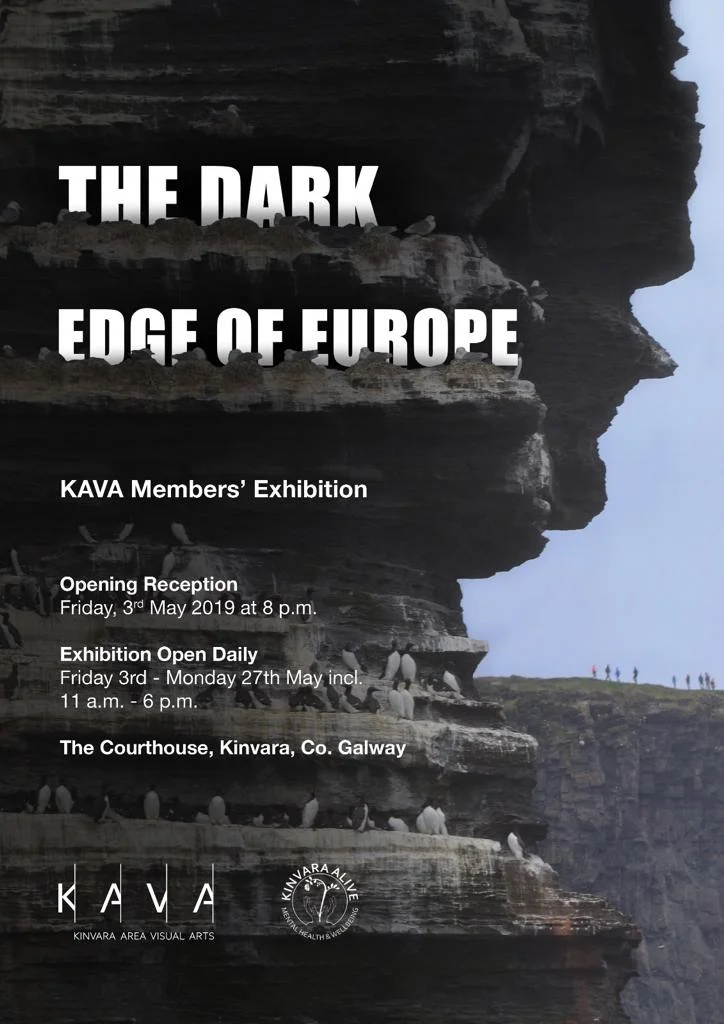

Before leaving the Burren for Donegal I visit The Dark Edge of Europe exhibition that I was invited to be a part of. This exhibition, with the KAVA artists, was coming to a close after four weeks in the courthouse gallery in Kinvara, a town at the northern end of the Burren. Artists met for twelve months to inquire into stories of sudden death from the Cliffs of Moher, the highest cliffs in Europe and a site often chosen for suicide. For research, artists took boat trips – around the base of the cliffs – and walks along the cliff tops. The exhibition coincided with Mental Health Month, Ireland, and donations were made to KinvaraAlive. (KinvaraAlive.com)

Each of the artists created work that responded to sense-of-place, and to the vibrant bird life that in spring seems to defy any sense of dispiritedness associated with the cliffs. My contribution was a sound installation, from recordings gleaned while in the Burren last year, added to and mixed in Hobart. I produced a CD that included other tracks from the Burren residencies. The two tracks composed for the installation, Shadow and Light, weave bird calls, improvised fragments, Irish tunes and a Bach excerpt that for me respond to a sense of lived despair, optimism, song and hope for connection. My good friend Emily Sheppard, violinist, added to the scope and quality of the recording with her serene playing of Seamus McManus’s Waltz and – in stark contrast of timbre – the Largo from Bach’s Solo Sonata in C Major.

Horn Head, County Donegal, Ireland

Horn Head looking towards Dunfanaghy

Ireland leaves

Autumn in Ireland. The Burren is under a blushed mantle. The trees are shedding their leaves, in the prevailing wind, but the scrub, fern and grasses are flaming in russet, saffron, and copper. As each day inhales towards the winter solstice the weather seems to tire of itself, to send variations. It’s rococo, and infectious in form and feeling. There’s some protection here in the valley from gales; however for me a ‘soft day’ will now be synonymous with iron-grey skies and misty rain and a quieting within.

Before I left the Burren I took a cruise along the base of the Cliffs of Moher, Aillte an Mhothair, joining a group of Clare artists gathering work for an exhibition. Our launch pushed through swell in driving rain and wind to then idle broadside to the cliffs, close to An Branán Mor stack. This year-long project - The Dark Edge of Europe - is the artists’ response to deaths at the cliffs, by suicide and accidental falling. I’ve been invited to join, as a composer.

The cliffs are nesting walls for breeding birds in spring: puffins, kittiwakes, guillemots, fulmars and razorbills. But in late October there are no birds on the stack; it’s a remnant in isolation, jagged and thrashed at its base by enormous waves. Squatting above, at the cliff edge, is Cornelius O’Brien’s round-stone tower. From the boat we spy walkers along the cliffs, miniature figurines. There are no guard rails past the information centre, just a path creeping along the brink. Many walkers stray from the track; inevitably there are slips, trips and jumps to sure-death. Boats patrol the cusp of rock and sea, searching for bodies. On this grey, dim day the cliffs loom in jagged patterning. Artists photograph the stack in the swell, the sloping grassed edge and the cliffs’ curvature, a spine sloping south, away, out of view. I record the boat’s engine but the wind in the microphone is so strong the throb sounds more like a whimper.

The tumult of the sea eases as we return to the harbour at Doolin, the town renown for Irish music, boating and changeable weather. There are many signs erected promoting the Samaritans. Dying off these cliffs has spread like a rash, as if the fable of living trumpets a call to dying in flight, one that ends where all life began, in the sea.

We leave Doolin, drive up over the Burren plateau all greyed in outcrops and walls, past Lisdoonvarna - the matchmaking festival town - down Corkscrew Hill, back to Ballyvaughan. I’m preoccupied with thoughts of staying alive.

I finish my residency with two performances and an open studio, for students and staff, to bear witness to two months of process, reflection and art-making. I attempt to write an artist’s statement and come to understand that everything here has been about relationship: to myself, to the studio, to new friendships, to this extraordinary eclectic art college, to the place of the Burren, to art as a facet of practising living. And so I write a thing that in itself is not quite formed, that’s obscure but also simple; like understanding that art comes from within and gives to others. This understanding, and the performances, have acted as précis to an unknowing that’s been almost impossible to quantify in my eight weeks here. Moments of doubt and self-criticism, tiredness, displacement, anxiety and a slippery hold on imagination have frequently dashed ice water on my art-making. As on so many other slippery slopes, improvisation has revived me, called me into the present moment and allowed the forming of sounds, words and gestures to be catalysts for peace, creativity and change. If ever there’s a sense of the sacred, it’s within the veil of improvisation.

https://www.cliffs-of-moher-cruises.com/news/seabirds-at-the-cliffs-of-moher

Artist’s Statement, Open Studio BCA, November 7, 2018

Bricolage

at/in/with…the Burren

Here i am, melting eight/8 weeks into a few skewed/skewered words for

You the observer/listener/visitor (…is this the haze of the gaze?)

You may also think/feel/wonder if You are the/an audience (as might i)

i’m performing/expressing fragments of knowing

from being at/in/with the Burren College of Art

in-studio/atelier

…

Knowing is

(has been and will be)

microbes of (…) &

Anything i write here will become new

soon

in 4 seconds (if we believe Daniel Stern of The Present Moment, 2010)

…

What have i been doing for 8 weeks in this studio/atelier?

gleaning…seems/seams gleams reams memes means

…dreams of words flowing… after i walked a bridge over an above-ground stream rushing through Rathborney valley (dis/close to here)…

an exception: rivers in the Burren are mostly underground…

i’m like a caverned water-course: images, sounds & gestures be/coming surfaces only to return to a hidden (riven) rivulet of pre-consciousness, unknowing…

(how does an ellipsis sing itself into oblivion?)

What you see & hear here is what you get…

fractures of fragility

fragments of failure?…returning to/for possibility & responsibility…

…beyond the wash-up of plastic amidst the demise of species under the weight of despair for a planet in contagion & Humanity swimming below a surface of Slime…

…improvisations from

yearning being stilling knowing learning weaving playing walking reading listening drawing sleeping weeping seeing laughing hearing making sitting sounding writing speaking longing remembering imagining feeling wondering disclosing harbouring forgetting leaving arriving losing finding colouring opening scoring gathering erasing creating loving recreating ellipting

hope resides in imagination

Haiku:

where wandering is

abundant surfaces from

rhizomes un-measured

North and South

The weather has shed its warmth and the hills are masked again in grey. I awoke this morning to drips pulsing in the downpipes. This ‘soft’ day is hurried by wind coming in off the sea. It’s not a morning for walking the limestone or working in the studio. I write in my room at our artists’ house, looking from time to time to the muted sky tones and the virulent green of the fields, waiting for abatement so I can tread the paths again.

I’m unspooling after a short furlough in the north. I took a long drive from county Clare through Galway, Mayo and Sligo to Donegal, along the coast, by farmland, through cuttings in tumbling rock. Donegal’s landscape might rival the Burren for beaches, steep slopes and stone but each place haunts the imagination. These places are more than landscape: they inhabit ecologies of climates, geologies, grasses, wildflowers, quiet cows, roads, tangled hedgerows, dancing crows, music and people. There is fragility and transformation.

The Burren College of Art and its signature form Newton Castle squat at the foot of Cappabhaile Mountain near the village of Ballyvaughan. It’s a home-place for artists, of any intention, where art-making is honoured and change happens. Students from art colleges in the USA, emerging and established Irish artists, alumni returning for scholarship residencies, and artists, like myself, on self-funded residencies are welcomed. The milieu is infused with goodwill and creative motivation and the land seeps into everything. Today, when the weather cleared, rather than visiting my studio I took a new way, through fields, along steep paths of brambles and hawthorn and farewell summer wildflowers until, wait…a row of bells on the hillside: five pipes, with red paint pealing back to reveal recycled metal, strung from a wooden frame. I banged the gongs with a beater on a string (an invitation), enjoying the decibels and tintinnabulation on the hillside on a Sunday afternoon. What can a sense of the sacred be? I recorded some sounds before walking further up onto the signature stone plateau of Cappabhaile from where I could see across the valley towards the eastern uplands and down to the village spire and the sea. The sun was warm and the breeze light puffs against my skin. Later, when I returned to the house, I added some drone sounds to the bells, a hymn from the earth and sky. Creativity follows me here, chasing me into webs and wantonness.

Donegal. Summer hesitates and autumn bequeaths russet on grasses, bracken and heather. Muting here gentles the largeness of things. The hills and coastline sculpt this place. I wander with a friend who knows the land well and takes me to places mapped by stories lived. We go to Glenveagh Castle, built by American money in the nineteenth century on the shores of a lake in the mountains. We take the castle tour and stand in a roundhouse used by people-with-profiles, like Greta Garbo and Charlie Chaplin; we walk through a food garden of linear proportions, built as if geometry matters; track through trees, on paths and terraces that fall away from the hills in the low autumn sun. A eucalypt stretches its boughs as if unsure of its place but is going to take it anyway: a moment of Australia in Donegal. The distant hills of the park fold their saffron mounds into each other. What is a castle for? A monument to success for the rich? Or a reminder that we can all share in wonder, whatever our class. It’s now a museum hovering on the brink of a beautiful national park, like the planet at the edge of precarious. We drove too along a tilting road, through moorland hued in cinnamon and bronze to a ruined fortress house, a Bastle, on a hill in a wide valley near a decaying railway line. Here was silence. And no invading tourists. Are they the new colonials? My studio became the rocks beside the stream and the dark stone cellars beneath the ruins.

We walk in Ards Forest Park, not far from the seaside town of Dunfanaghy. Near the shoreline I feel a tinge of belonging in the light spinning across the trees that lean away from the wind coming over Sheephaven Bay. The unkempt woods (that I’ve missed in the Burren) remind me of the forests in Tasmania that I’ve fought for so long to protect and yet they are still at risk of decline from logging. I know so little about Irish native woodlands and a bit of research assures me there is elm, birch, oak, ash, rowan, yew and hawthorn, with introduced species that include chestnut, sycamore, beech and stands of spruce. There’s rhododendron too, but it’s a weed, choking many plants. And I see ivy, pulling at bark and spiralling up trunks and along the forest floor. I want to rip it out, as an invasive weed, but I see it has a delicacy here in this forest, with all these European trees, like its familiar filigreed attention to ruins and neglected gardens. How to translate Tasmanian ecologies to knowing this place? I feel subsumed in the new and strange, awake to how being here might let me be there: more present and awake.

Yesterday I took the bus to Galway with my residency house-mate and we had lunch in The Front Door pub. It’s a warren of caves made all the more mysterious with Halloween decorations, stairways and archways that lead deeper and deeper into caverns. I’ve never been in a pub like this in Australia. It’s on the cusp of spooky and magnificent. We walked the laneways and I had a haircut in a barbershop because hairdressers were closed for a fundraiser (for a local family affected by tragedy) or else fully booked. My barber was a Syrian refugee, from Aleppo, a universe away from this calm, prosperous town that’s known other kinds of pain. Ireland, oh Ireland.

Chimes on Cappabhaile

Bastle, Fortress House, Dunfanaghy, Donegal

Glenveagh Castle, Letterkenny, Donegal

The Flaggy Shore and other Burren burrows

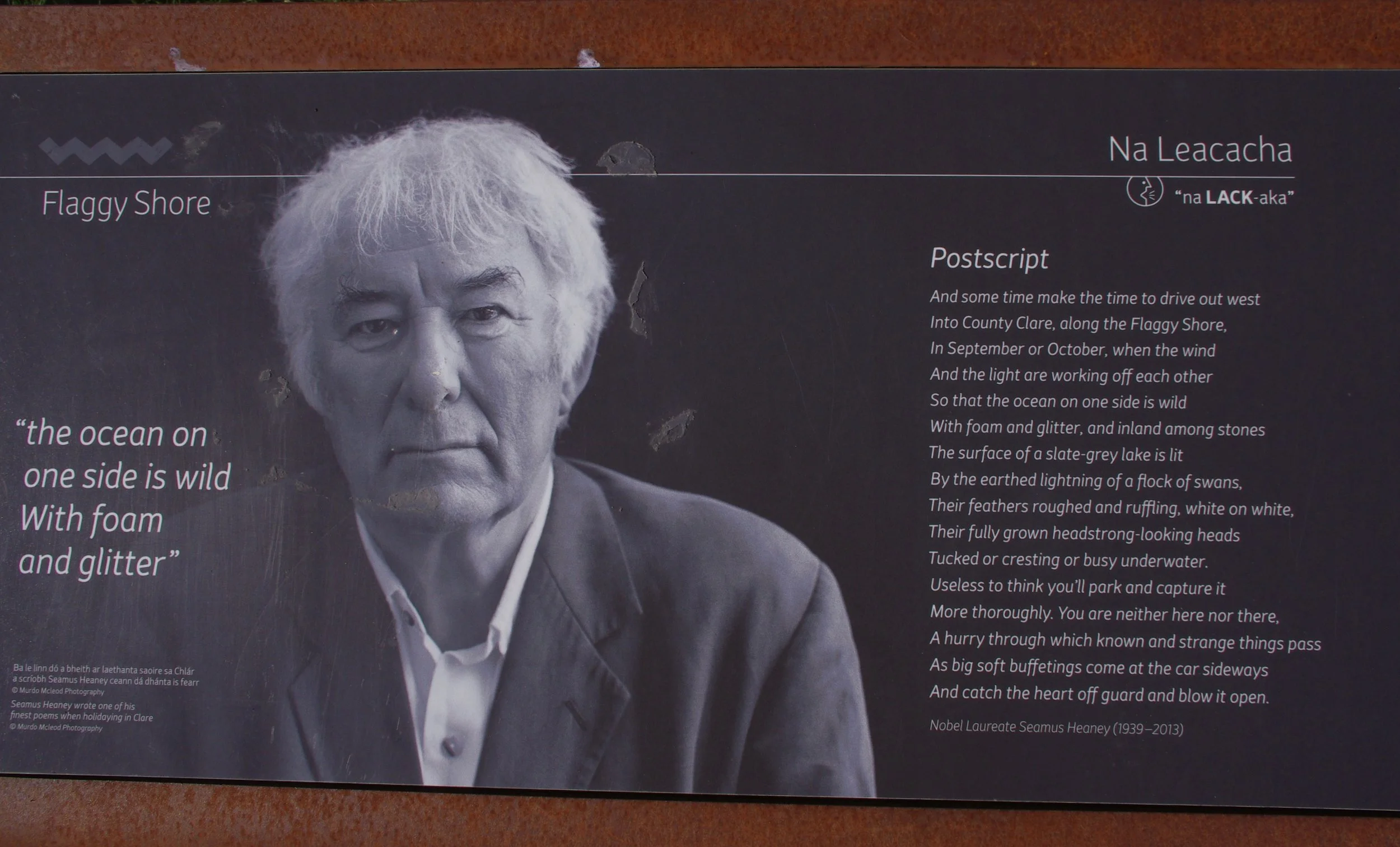

A few days ago I visited the Flaggy Shore with another artist-in-residence, Peter, a sculptor from Ohio. At the start of the Flaggy Shore road is an interpretation board with a large image of Irish poet Seamus Heaney alongside his poem Postscript:

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

So that the ocean on one side is wild

With foam and glitter, and inland among stones

The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit

By the earthed lightening of a flock of swans,

Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white,

Their fully-grown headstrong-looking heads

Tucked or cresting or busy underwater.

Useless to think you'll park or capture it

More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

The poem catches my heart off guard before I have a chance walk the Flaggy Shore. But its shimmer and immediacy has been popularised for spectators. I’d heard this poem read aloud at an Irish education symposium the previous week. Then it had seemed so necessary and appropriate to the “presencing” praxis and ethics we were all experiencing while interrogating ideas for creative transformation in the school system and connecting with each other on matters of the imagination. I walked along the Flaggy Shore with Peter, after coffee and tapas at the café, unsure of what a flaggy shore should signify, intrigued that this strip of unremarkable coastline has grasped tourists’ urgency of attendance. It was a weekday but there were many viewers on the narrow road. Oh the voyeurism of tourism and its discontents. Has the commodification of Heaney’s poem added to making this site/sight so magnetic? It’s as if we are being asked, and increasingly, to view a series of bodies along a long line of preordained topographies. But what is between, off the track, quiet, or roaring underneath? How do we open our minds (and hearts) yet stay on track without distraction?

We met two women, coming from their daily swim, who told us to avoid the area on weekends because the traffic is pressing walkers to the wall, literally. Last Sunday a car hit a child’s stroller and the driver, angry at being slowed down by walkers with children in strollers, then provoked an altercation with the parent who was understandably very reactive and distressed. Fortunately the child had been removed from the stroller just before the incident. The women told us they are part of a campaign to reduce the flow of traffic along the road and have been removing “Atlantic Way” tourist signs that point to the Flaggy Shore. Ah the activists! They blow my mind.

It was a day for shocks. One of the women, when she heard Peter’s American accent said: “I love Trump!” And then she turned to me smiling and said, in her Dublin brogue, something like: “Don’t you just think he’s such a fine hunk of a man?!” In that moment I realised how much my political views are reinforced by my associations with those who hold values similar to mine. This was a moment for coming out: about how much I hate Trump and all he stands for, and how the language he uses is so toxic that I now stanch it before it putrifies my skin, and that I find his arrogant capitalist dissembling puny and bileous. Our conversation was rescued, from catastrophe, with humour, and so we admired Zinny the 17 year-old Jack Russell perched like a queen in the bike basket.

I watch the tourists walking along the Flaggy Shore road, intent on reaching the next café at the other end. The beach is famous for fossils. A young lad dances along the beach, stops to look at rocks before running to catch up with his family. We pause to take photographs of the gradations in rocks, kelp, grasses, cows’ coats, sea and sky: artists forever thirsty for beauty, colour, change. I’ve come here as a tourist too, not because of Heaney’s poem but because I’ve been seduced by publicity, the blot on the map, the magnet to funnel into “same”. What would Heaney (or another poet) write, about this phenomenon? What would blow a poet’s heart open at this smirching of the extraordinary in the ordinary? I think of the coastline of the Tarkine/takayna on the west coast of Tasmania, of the middens desecrated by vehicles, and it resonates like a clanging. It’s the voyeur in the landscape: a common denominator view minus appreciation (and protection) of what’s really there (past, present and future).

Last weekend I walked the Burren uplands with some keen Irish walkers in glorious weather. How many times did I hear “What a Beautiful Day for It”!? (Since then it has rained most days). The leader was a Clare farmer whose like-the-back-of-his-hand-knowledge left me in no doubt he knew where he was taking us: up and over Gleninagh Mountain to Black Head and back to Ballyvaughan, mostly off tracks. I felt like I was measuring every step to keep the tail-end alive and return with normal ankles. Our only stop was a fifteen-minute lunch break, on the top of the mountain, in a chilling wind overlooking Galway Bay, with Black Head - the Burren coast promontory - a long way below us. We pushed fast up steep slopes to criss-cross the uplands, step over the grikes (holes in the karst limestone), teter on the loose clints (pavement blocks) and thump down the pitted slopes of grass like the goats that live up there. This was walking with serious intent: to finish. Did I mention that some of these walkers were training for the Himalayas? I didn’t find that out before setting off.

Last week at the symposium I had the pleasure of meeting and listening to Martin Hayes, virtuoso Irish fiddler from the band The Gloaming and other bands. He was the special guest, to synthesise our discussions into poetic and musical form and he did that like a laureate. I had the pleasure, at a “session” of playing along with him and a local harpist in a couple of tunes. I felt as if I was swimming in one of those rare moments of bliss. It’s difficult to listen to other Irish fiddlers now after hearing his intuitive response to the moment and his tenderness for every note. Last night at one of the local hotels two fiddlers played reels and jigs in unison for several hours, like wallpaper. Where was the phrasing, nuance, space between notes, expressiveness and communication? I admired their capacity for endurance and memory but couldn’t stay long in the room to listen or think of joining in.

As US pianist Thomas Bartlett, says (quoted on Hayes’ website): “I remember the first time I heard Martin play, and there was something that happened to my body that I hadn't experienced before, where I felt like my heart would expand and contract with the way he was playing." Blow it open!

https://soundcloud.com/the-gloaming-official/the-girl-who-broke-my-heart-1

Newton Castle and looking east, Ballyvaughan

Seamus Heaney at the Flaggy Shore

The Flaggy Shore looking towards Ballyvaughan and Gleninagh Mountain

Looking east from Gleninagh Mountain, the Burren, County Clare.

Burren...

These last two weeks I’ve translated my identity between places: Hobart-Melbourne-London-Dublin-Belfast; to my mother’s cousin’s farm in county Derry, and to the lakeside in Fermanagh, near my father’s ghosts and relics. Now I’m back in the Burren, county Clare, peering through my studio window at the tower house. Grass grows between the cracks and from the sloping base, like our histories, stories, places, wars, lives, deaths, and families, with all their multiplications: an endless cacophony of subjectivity.

A storm from the North Carolina coast was forecast to burr across the Atlantic and slap into the west coast of Ireland last week. It came at first with an apology: light rain, spinning wind and “humid conditions”, which in Ireland is 15 degrees. I looked out on scudding clouds, teasers of blue and trees considering autumn. I hoped the weather would brighten. A day later Ali crashed the coast, the first named storm of the season: 140 km winds hit during the night and blew away a Swiss tourist’s caravan, with her inside. She died tumbling the cliffs, crashing into the surf below. Imagining such a death, and in the dark, I sense stupefying terror and isolation far beyond possible apprehension. Here in west Clare we stayed inside while trees resigned from vertical and rain fell like lead sheets. My brief excursion in my car to an early morning yoga class felt almost suicidal. The weather delayed the ploughing festival in Offaly, an annual event that celebrates rural life in Ireland, tine by tine. It’s the biggest outdoor event in Europe; fortunately it’s a long way from here or our roads would have been as clotted as those in Tullamore. Here in this farming community there are many tractors and machines finishing silage harvests before the grass dies off, as weather cools, and when cattle will be sent to the Burren uplands for wintering.

The tower house remains vertical, in all weathers, unlike the Albert Memorial clock tower in Belfast that is leaning; is it to the right or to the left? I took a walking tour in Belfast, one of my rare participations in organised tourist projects. A historian, who was 10 when the Troubles were at their most troubled in the 1970’s, took us on the History of Terror walk, pausing at significant sites to tell stories of terror/ism. I had visited the Troubles display at the Ulster Museum the previous day and still felt emotionally withered in response to the images and narratives commemorating the 1968 civil rights march from Belfast to Derry and the marchers’ traumatic grief at the launch of sectarian insanity at that march.

We walked to the site of the Abercorn bombing of 1972, where two young women left a bomb in a crowded family restaurant after being denied entry to the upstairs bar. Two people died and more than one hundred (mostly women and children) were seriously injured in the explosion. The bombers have never confessed nor been found: I wonder at their lives, lived in the wake of so much destruction, desecration and physical and mental trauma. I was stirred by the story of one of the young women who died that day, whose name was Breen (but later I found it to be Bereen), and whose father, a doctor, was on duty when she was brought to the hospital.

Sectarian conflict surpasses, to me, any notion of what religion, of any stripe or band, might represent. To be so cast in metal, without any notion of alloy or humus, disturbs my sense of what it means to be human.

A butterfly has come into the studio.

View of the Sperrin Mountains from the gate of my grandmother’s farm, Co Derry.

Newton Castle, Burren College of Art

North of the equator, again...

Ireland 2018. Returning to the greener land…

I’m stopping over in London enroute to Ireland, writing this in a Thai restaurant, sitting next to a black woman, listening to a conversation between a black man and a white woman. I’m staying on the Portobello Road. Each day more market stalls appear until by the end of the week most of the road is patched with stalls. I buy a soft toy for my grandson from a cheerful man with a Caribbean accent. I wait for him to comment on my Australian accent but he does not. Everywhere I step in Notting Hill there are (by way of my observations and presumptions) variations in language, dialect, inflection, skin-tone, class, housing, sexuality, costume and pace, including my own.

I’m neither rich nor poor. I pretend to be working class (when not); I understand what it means to be an ageing, middle class white woman in the twenty-first century; I think I get racism but I’ve never experienced it and probably never will.

I’m reading Robin Diangelo’s ‘White Fragility’ and have come adrift in my attitude: that I live as non-racist, anti-racist and humanitarian. I ask myself now, how DO I live a life - from a white perspective - without projecting (and assuming) its inherent privilege and power? What do I need to do to understand just how life might be ascribed to someone as ‘other’. What does ‘other’ mean, for me? Can I lose my self-consciousness around racism, shed my defences that are embedded in centuries of white traditions of ownership and individuality? I want to merge, to feel like one of ‘them’, but who are ‘they’? If I have white skin, privilege is ascribed, assumed, inherited; my habitus is white supremacy, despite, and including, my defences, my ‘Fragility’.

I walk the streets of Notting Hill, admiring the confidence and ease of black and brown women and men and feel glad. I’m summarising interactions like a sociologist, hyper-alert. Why do I not observe and describe mySelf, and fellow white citizens, with the same intensity? How can I be so superior and racist in my thinking? Because: I inhabit the ‘white racial frame’ of internalised superiority.

I’m reflecting deeply on this, since reading Diangelo, but I’m not sure how I can work on transformation. Something has happened to me around race: my fragile assurance is eroding.

An old Irish man sitting next to me on the plane yesterday heading to Dublin refused to use his seat belt even when asked by the steward. He held his hands over his waist, pretending, for the whole flight and laughed and called me “darlin’” when I suggested he do it up. I guess not all of us have a fear of flying.

(see White Fragility: Why it’s so Hard for White People to Talk about Racism; R. Diangelo, Beacon Press 2018 ).

Portobello Road

At the Battery, Bellerive Tasmania

The sun stems July’s chill. It’s mid afternoon, two weeks after the solstice. Hobart glistens across the river as if summer is more than the future. I’m standing on a mound above the trenches that border the old fort in Bellerive, on the eastern shore of the Derwent. Two of the original four canons remain, pushing into the air above the stone walls like scalpels. The place has been renovated to a heritage park, with new stairs for safe entry into the corridors that circle within the mound. Each of the “rooms”, dark cloisters underground, are gated, locked to prevent graffiti artists, paedophiles and murderers.

As I move from the car towards the battlements, I notice a man holding a drone. I hesitate, thinking I do not wish to be interrupted, but I move on because he appears disinterested, getting ready to leave perhaps. I walk up and down the corridors, searching for a resonant space to play my viola. I unpack in a circle where a canon has been removed, leaving a broad ring of stone and concrete. Although the walls have been patched, mortar fragments litter the ground, crunch as I press my feet into them. A eucalypt stretches into the space between the wall and the sky, as if talking back to the possibility of violence here, in this quiet suburban street. I begin to play and at that moment I hear the drone, like a wasp, overhead. There it is, white and quivering, fifty metres above me. I move into the shelter of a wall, aware I cannot hide because there's no overhang or roof in the ramparts. I turn my back to the drone and accompany the whine, playing ponticello, or sul pont, on the A string, mimicking the microtonal movements in pitch. Whatever the photos reveal there will be no sound, just a woman in a black beanie, on a Sunday afternoon, in the ruins of a fort.

The drone retreats. Perhaps I sent it off with my glass-notes. I wipe the strings again, something more melodic, keeping the bow at the centre of the strings, digging in to make a big sound. I hear voices. “It’s a lady, playing the violin.” “Hello,” I call, and continue playing and making up poetic lines. The man and the small girl climb up the mound above the trench and walk towards the tree waving its branches like arms. He is telling her about the old ships that came up the Derwent, and of the canon, as if they speak for this town. She runs, singing, into the distance, playful, dismissive. I play on and on.

Mount Field in autumn

Mount Field Tasmania, April 2018

The wind across the plateau scarifies. We wrap the baby’s head and bury him deep in a carrier attached to his father and walk to shelter under snow gums on the shoulder of the mountain. We’ve climbed to see the deciduous beech, fagus (nothofagus gunnii), in autumnal costume: beryl-green, crimson and turmeric; but today, at Tarn Shelf’s gallery, wind has stripped the stand and so we descend, disappointed yet elated to be once again in this elemental fury and alpine beauty. The northern horizon is a spine of blue and the forested ridge to the near-east is scarred with escarpments. We prop under the trees, beside boulders with lichen etched into surfaces: white, black, orange. I stoop to photograph a circle almost perfect in perimeter. It glistens like a moon. Snow gums startle with palettes of bright-red, saffron, and magenta and we moisten bark patterned calligraphy for better photographs.

Out of the wind we relax, bounce the baby on his new legs – now he knows walking is not far off – and drink warm tea with our sandwiches. Near the summit, in the roaring gusts, tradesmen push the new information centre into the levelled clearing beside abandoned ski slopes. The concrete curves present a formidable edge to the alpine world. The edifice will survive, perhaps long past the climate-change age and the demise of snow sports.

After lunch we descend the long trail in the spinning wind, through a quiet grove of pandani (richea pandanifolia), hair-like fronds trailing beneath its strap-leaves. At the huts we cluster near the fire, and wait for abatement. It comes at midnight, a whisper. At sunrise, stillness. A mist cousins the pearling of the gap between the hills. We smile in wonder and delight.

snow gum

snow gum

lichen

pandani

looking north-east at sunrise

fagus

Late spring in Tasmania

Spring in Hobart, 2017 (and recalling a month ago)

This spring, snow has regularly delivered its topping to the mountain in defiance of impending warmth and prophecy. Today (early October) the cold breathes down into the city as if we’re summering in Siberia. Daffodils lining footpaths have browned off and the boughs of wattles that have been gilding the valleys for weeks are spilling their wares. Soon these trees will be reddened with seedpods. Hellebores are nodding sepals and the maples, after wintering bare, renew with céladon vigour.

Predictions are for a warmer than average summer. Last week I travelled to the Fingal Valley, near the famed beaches of the east coast. News of fires there, in late October, has pushed forward the calendar: it’s as if we have fallen into January.

“Any rain is welcome,” says a farmer, as I walk a wide brown path between green fields and stop to make conversation at a cottage gate. “This green is superficial. Soon it will all be beige,” she adds. I keep moving, keen to finish the line that reaches a fence keeping Angus heifers within limits. They stop as I pass, motionless in curiosity. I envy them their stillness. The severe escarpment of Ben Lomond, north of the valley, is like an image from the Romantic Sublime: evoking a realm beyond my existential reality and the immanent drought. Later, my friends return from a drive to Ben Lomond's summit, their necessary excursion before heading back to Western Australia and its flatness. I’ve never been to the west and, if it's as flat and hot as reputed, I’m not wanting to go there, not yet. The ascent up Ben Lomond was reviving, the summit spoke, my friends said. I'd warned them of the horrendous road, Jacob's Ladder, but they only mentioned the calm and bliss near its end and, that temperatures were mild - "like down below" - and that the diminishing snow offered just enough contrast to satisfy.

I return to Hobart through the midlands, thinking of Ireland's fecundity as I drive between fields greened by light spring rains. Next time I come here, if in summer, this valley will probably be brown and Ireland a gallery of green.

Ben Lomond from near Avoca

Returning

Hobart’s hills are distinct through stripped trees now winter has come. I’m transitioning from Ireland’s long, bold twilight to this soft darkening. Dusk is known as “dayli’ gone” in Ulster-Scots, poet Michael Longley told us at his reading, and back here in Tasmania it’s as if the day has barely awoken before it’s gone.

I feel wistful and somewhere between worlds. This liminal mind lumbers into routine as if for the first time, re-convening roads, time-zones, people, work and radio stations. I miss the Burren and its mauve shadows that are as gesso to everything in the foreground. Vestiges of autumn’s tones and the frosted morning grass remind me of where I am, not in the glow of Ireland’s west coast. As memory fades, longing returns and the prevailing sense of exile drifts again into my orbit. How is home remade?

As I breathe into returning to the hem of the world - and a limping Commonwealth - another election is re-fashioning the UK. Jeremy Corbyn, the much-maligned-by-media candidate is reviving the pitch towards best-for-all while Prime Minister Teresa May falters and will align with the DUP in Northern Ireland to arrest her ship’s tilt. Ulster is so often forgotten in political scrums and now its chance to bolster Britain may revive simmering sectarian fear. Will a United Ireland emerge from the dust or will the motes explode in its face? No-one wants a return to hard borders on the island of Ireland and I’ve read that the border may now move to the Irish sea rather than reappear on the roads. The majority of farmers in the borderlands voted to remain in the EU and although Brexit is now inevitable, and a hung parliament in Westminster complicated, perhaps transitions might become more equitable. Ireland is like the supporting character in a narrative of hope within a spectacular history of survival.

Tasmania’s winter-green tone is not the emerald of so much of Ireland yet its prevailing presence is almost as comforting. The eucalypts, blackwoods and silver wattles along the banks and hillsides are dusky, almost blue-grey, as if reflecting the sombre winter sky. As I watch the gulls circle across the slopes of kunanyi, Mount Wellington, before they return to the estuary at dusk, I’m reminded of patterns and rhythms in nature and of how they represent so much hope. The winter solstice is one week away and celebrating it is a welcome rite in 40-plus latitudes. David Walsh’s fireside festival has become an institution: not only for transgressions in art but for transmission towards warmth and light. While we farewell the longest night, in Ireland the festivities will bid adieu to the shortest night, with song and dance. We hold hands across the planet.

Australia has its distinctive animal characters that mock and manifest whatever the season. Kookaburras nearly fell off their perch laughing as I jogged past them today. Can laughter be the collective noun? A conspiracy of crows and an ostentation of peacocks made it into the lexicon; a laughter of kookaburras? And what of currawongs, those charcoal ravens that swoop into the city’s fringe as snow-clouds build across the mountain, their falsetto calls screeching as if commanding law and order. Their sound is unique to Tasmania and one I associate with walking through forests or camping near rivers in the mountains. Like the cuckoo in the Burren, the currawong speaks to being where I am and to listening.

Eucalypts in the suburbs

kunanyi/ Mount Wellington in winter

Dark Mofo Hobart 2017 light show

Ellipsis

The lavender hills. A few days ago I joined a valiant brigade of walkers across a northern part of the Burren. Every Sunday, whatever the weather, they hike the hills. Along the way there were many conversations: living in the Burren, walking the camino, education in Ireland, Syrian refugees in County Clare towns, Irish politics, music, history, Tasmanian devils and Burren geology and botany. We walked up and across the limestone pavement, past several medieval ecclesiastical sites: Corcomroe Abbey (1194), Colman’s holy well, and the Oughtmama churches. Monastic and church sites in the Burren seem almost as profuse as the wildflowers. The stories lying latent are various, many tragic, such as the graves of children who were not baptised and the deaths of teachers of hedge schools caught by the redcoats for delivering illicit education to children (in the seventeenth century).

To be here in spring is to be surprised by colour at almost every step: in gaps between rocks, under walls, beside pathways. Hawthorn is abundant, festooning fields and roads in white and pink clusters. As May moves towards summer, wildflowers decay on the slopes and valleys yet are still resplendent: spring gentians, orchids, bloody crane’s bill, hawthorn, primrose, dog-rose, wood anenomes, mountain avens, wild strawberry, cowslip, bird’s foot trefoil, dandelion, germander speedwell and many more with wondrous names. Walking and looking has many rewards. After Sunday’s walk I purchased a guidebook to wild plants of the Burren. I’m gradually coming to understand differences with Tasmania’s unique ecology and the need for informed stewardship in both places.

The Burren is a Geopark, one of a network of important Geoparks in Europe. BurrenLIFE, a program funded by the EU, has been nominated for a Green award for its “phenomenal impact on a unique landscape.…[because it has] pioneered a novel approach to farming and conservation…with alternative approaches to sustainable management of high nature value farmland.” Its premise is building a sustainable relationship between agriculture, community and ecology. It is educating farmers and businesses towards bringing into focus the uniqueness and fragility of this environment. BurrenLIFE, in process now for 20 years, works from a simple principle: cattle are taken to limestone uplands in winter to eat down the grasses instead of being fed silage gleaned from fields. Reducing growth on the hills by grazing favours the wildflowers’ appearance in spring when cattle are returned to the lowlands. Farmers are rewarded financially if they support the scheme by not overgrazing, maintaining the stone walls, controlling overgrowth and reducing use of silage.

Grazing in winter on uplands seems counter intuitive and in reverse to other European countries with traditions that transfer cattle to highlands in summer; and in Australia cattle are reported to be totally destructive in fragile alpine reserves. What has been highlighted to me here is that ecology is niche- and place-specific: it needs stewardship that is unique to that land. Wintering of stock in the Burren has seen the return of bio-diversity and a deep pride in land care. Diversity here has a broader meaning than in Tasmania where endemic species are seen as necessary to protection and everything foreign excluded. Here conservation and biodiversity has a broader agenda. Dialogue with those who live there, or who have deep ancestral connections, may take time but is richly rewarded.

The Burren in Bloom festival (for two weeks) and the Burren Marathon (this weekend) offer a plethora of choices for visitors and locals in May. A real joy for me was attending a reading at BCA by Belfast-born poet Michael Longley, contemporary of Seamus Heaney and winner of many poetry awards. He chose poems of place and all referred to flowers, many he had found in the Burren. His gentle and meticulous poems speak to his love for this wild garden as well as to the pain of experiencing the Troubles in Ulster when he lived there. I was deeply moved by this poet’s reading, particularly since my recent trips to Belfast and County Derry have established a vibrant connection through family with Northern Ireland.

The singers in the whiskey bar last night spoke of the sadness so many of us were feeling following the Manchester bombing this week. So many Irish know that city well. Songs from the American songbook of the 70’s and 80’s dominated the visiting singers’ choices. Irish songs, sung by a couple of regulars, men in their 80’s, were of work, love and loss: poignant and memorable. I wondered about singing Lee Marvin’s “I was Born under a Wandering Star” and Don McLean’s “Bye Bye Miss American Pie”, songs that I didn’t rally to when they were popular but last night gave us all opportunities to sing together. The goodwill of the song leader was evident: to raise hope and deflect depression after so much unnecessary loss. Let the flowers bloom: Burren gentians, dandelion, hawthorn and Tasmanian laurel, scoparia and the brilliant fagus leaves.

My time here is closing in. In two days I will be returning to the Southern Hemisphere, to Tasmania’s mild winter. Daylight will diminish. Here light is like an endless festival, birds its constant chorus. I will light a fire, sing and play Bach, improvise inside and outside, marking my return with the sounds and silence trawled from my brief time in Ireland’s arms. My memories of the Burren residency will be of many hues. I’ve taken this place deep into my being and I’m so grateful.

BurrenLIFE:

Fern on the uplands limestone

Hawthorn near the ruin of churches

Gentian

Burren clints and grykes in its karst landscape

close relations

The weather here is like an old coat: familiar. But I’m weary of its chill. Today the cold wind is a broom, endlessly sweeping. Several days of sunshine warranted celebration until the absence of rain began to feel empty. And so there has been rain at last, as pundits predicted. The grass in the paddock I walk through to the studio is blistered with damp. Walking on wet limestone on the hills is treacherous: it’s very slippery and so I measure my tread or wait until the rocks have thoroughly dried before gaining altitude.

Daylight extends past 10 pm and I love watching people walking about in the evenings, popping into the bars in the village. There’s one supermarket and four pubs. The crowd gathers at O’Loćlain’s whiskey bar from 9 and music often starts around 10, but you can never be sure. Last week, word got out that two musicians from Dublin were coming. By 10.30 songs were bouncing off the walls of the small space and I didn’t get out of it lightly. I was instructed to sing something Australian and the only nationalistic song I could think of was Waltzing Matilda (the alternative version). Patrons were welcoming and generous and the visiting song-leader more of a stand-up comedienne than a singer. Folk from Clare (also known as Banner country) will sing ten verses of a ballad without reserve. It’s a practised art.

I tarry in my large, bright studio overlooking the courtyard and round tower house. I’m writing, composing, painting, playing Bach; I’m privileged to be old enough, young enough, rich enough and able enough to be here. Each day is like good coffee or a fine book: endings are a disappointment. There are groups of visiting artists hovering in studios alongside the gallery at the college, taking classes on looking at the Burren. Their teachers are painters and BCA lecturers, past and present, who know this remarkable landscape and have exhibited internationally. The two other artists-in-residence head to their studios each day to probe their imaginations towards production: one in sound, the other paint. We hover in conversations outside the café, on weekend breaks from “work” and in our dwellings.

Swallows swirl past the windows looking for nesting potential. They’ve moved away from the tower at the request of Robert the concierge. The Burren is a sanctuary for birds. although many are in decline due to loss of habitat. Last week, and again today, I heard the first cuckoo in spring, moaning for a mate. Now I understand why Frederick Delius wrote his tone poem On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring. It’s like a call to attention. Mary, the college president, told me that by the end of summer the cuckoo’s moan becomes a raspy, feeble drone. Does that signify cohabitation? They remain hidden from view so who can verify relationships? I’ve purchased a pocket book on European birds to try and identify a mysterious call I heard on the hill behind the college yesterday. I thought it was a machine: two loud, low tones of the same pitch and five minutes between calls. Too industrial-sounding for a cuckoo; similar to a lyrebird in mimic. But the book has not so far enlightened me. Tonight I’ll be attending a talk on trees by a Burren arborist…he may know the bird call.

I’m reading American-Irish writer Rebecca Solnit’s A Book of Migrations: Some Passages in Ireland, her journal of walks, talks and history in the west and south coast. It’s a wonderful read. Rebecca and I have each acquired Irish passports thanks to a grandparent who lived here and the generosity of the Republic. (To now obtain a passport in Britain your father has to have been born in the UK: a misogynist development?). Ireland, the country that claims us, invites exploration, to muse on what Solnit calls “mythologies of blood, heritage, and emigration”. It’s hard to know which of those three mythologies (and historiographies) figure most in this land. There’s a continuum of movement and stability here that’s hard to define or understand. Almost everyone I meet has either lived in the USA or has relatives there. Many have family in the UK, Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. There are very few with dark skin. I plunge into reverie, thinking on whiteness and the assumed privilege of the western world and on the obstacles for refugees to gain entry into USA, Europe or Australia. When my grandmother emigrated to New York from Ulster before the First World War - a (white) poverty refugee - she required no visa or passport. How would she go now? Irish immigrants are treated well now, compared to post-Famine when they were often locked out of employment or given the lowliest of jobs, as were so many with dark skins. Many Irish immigrants kept strong ties with Ireland and the Irish language (and continue to do so); it was partly due to the American-Irish sporting club (GAA) financially supporting homelands that Ireland gained independence in 1922. Ulster of course remains an anomaly of Europe (soon to be in exit with Brexit). Is a United Ireland immanent? And will skin colour become less homogeneous?

In Tasmania narratives of black and white relations are mostly of white domination but there are courageous stories of indigenous activism and hope that continue. When French explorer Marion Dufresne came to Tasmania’s east coast in 1772, contact is reputed to have been initially friendly. I imagine a new story: Aboriginal landowners reaching out a hand of welcome. From what little I know of the encounter, visiting French sailors and the residents of Cape Frederick Henry Bay had conversations and exchanged gifts; but sadly, violence to the Aborigines then ensued. And what then? The British, in 1788, decided on a penal colony in Van Dieman’s Land to pre-empt French settlement. How different Australia would be had the indigenous residents set the rules for entry, engagement and citizenship. The significance of the fight to protect takayna/the Tarkine on the west coast of Tasmania is a call to justice and collaboration for a land embedded with stories and land-marks of the people who lived there a very long time.

There’s a sense of return here on the west coast of Ireland: each day the number of tour buses seems to increase as days lengthen and warm up. I hear American accents and wonder how many of these visitors are curious about ancestral homes like I am. Place is a flexible state of mind; or discreetly obscure, like the cuckoo’s.

The garden at the Perfumery, Burren uplands

Ballyvaughan, looking along the Atlantic Way towards Black Head and Fanore

Fanore shoreline

Fanore's shore forgot to be bland...

how will it withstand

this saffron sand?

I visit Fanore

where sand

weeps

The rocky shoreline at Fanore, looking east, towards the Burren hills

Fanore shoreline

water colour on gelp

Newton Tower balcony improvisation

rising form...

Islands

It hasn’t rained since I came to County Clare. There’s a fire in Connemara, across Galway Bay. I’ve come to Inis Oírr on the Aran islands, near the Cliffs of Moher. A weaver, who has lived here all her life, shows us her loom in the front room of her white-washed cottage in the village. She weaves variations on the same piece every day, like a dedication. It’s a miniature tapestry of her vista across the bay she tells us, as she points to the scene that today is indistinct and grey from smoke. It’s dry! she says. Water restrictions are in place. At the hotel next door, the publican, who is from Australia, says it’s only level one restrictions and that’s nothing compared to…last winter he lived through five months of continuous rain. He wants another ten degrees of warmth and plans on returning to work on the Great Barrier Reef once his missus, who grew up on Inis Oírr, receives an Australian visa. He remembers how to make a flat white (but it’s washed out, bleached, like the Barrier Reef, I decide). The fire in Connemara is threatening the National Park and hundreds of hectares of forest have been destroyed. Farmers, attempting to wipe out gorse without permits, started the fires, so a local man in Ballyvaughan tells me when I return from the islands.

My companion and I walk on, as far as the road goes, through a grid of rock walls, past a food van and a shipwreck, an incongruous juxtaposition on this remote Aran island coast. The kelp washes in and out against the limestone shore. I remember the kelp in Tasmania and wonder if this kelp too will die as water temperatures rise. We hesitate near ruins of a castle then circle back towards the harbour, passing cyclists, tourists like us. Most of the houses appear to be empty. Are they summer houses? We pass a playground cheerful with children near a building we assume to be a school and walk towards a group of young girls who ignore us. In a steep field two women are rolling a large pallet towards the road. A dray pulled by a draught horse swings past us and the driver asks us if we want a ride. We decline, as we have to other offers. Viewing the island from a horse and cart is a quaint idea but I can feel my resistance to tourist-cliché rising. We order coffee at the tea house. It’s good strong coffee and the woman serving it has a wide encouraging smile. Suddenly I hear Irish being spoken nearby. All the signs in the village are in Irish and I noticed an na Gaeltacht sign near the wharf. I want to protect this place from the extremities of tourism but I’m guilty as charged: I’m an outsider looking in, making comparisons. On the way back to Ballyvaughan after the ferry, we stop for craic in the Fitzpatrick pub in Doolin, reputed to be the music centre of the west coast. I yawn through renditions of Neil Young and the Carpenters by a guy who plays as if he's forgotten vigour. After he packs up three young traditional musicians set up; two arrive late to cheers from the full house. The uilleann pipes, wooden flute and guitar take flight from the bards that play them. This is good craic. I'm revived.

The road to the wreck: Innis Oírr

Kelp on Inis Oírr

The beauty of the past in the foreground against smoke from the Connemara fire that obscures the Cliffs of Moher (the most visited site in Ireland).

Tower weave

Beyond the edges

a bird

within these walls

a song

Soundings and roads

The Burren sings. Today, I wandered into the field behind the college and held my viola towards the wind in the silence: an Aeolian harp, faint, but distinct. A flock of ravens interjected, followed by a jet and a moment later cows began bawling in the corner of the paddock and a tourist bus groaned up the hill towards the Cliffs of Moher (30 kms from here). Silence is never total.

If there’s anything I will be unable to eradicate from my memory of Ireland it will be the roads. Historical documents record that during the famine in the 1850’s, and at other times, the English forced the indigenous locals to build walls and roads in the Burren for obsolescence: colonial abuse of course. Walls, where no stock graze (because it’s all stony ground), creep vertically over the limestone hills and roads crosshatch the land like nets holding in the surface of the country.

Unfortunately, in this area, even the major roads are like laneways, with no shoulders for walkers or pull-offs for cars. And they are edged with stone walls. We have been admonished to wear high-viz jackets if we walk into the village and not to walk at night. But a high-viz jacket can’t be seen around corners. Today I leapt over a stone wall into a cow paddock after a near miss with a car and then walked over boggy ground rather than continue my suicidal stroll. To upgrade such a system would be impossible but surely a few footpaths could be considered?

My walk was rewarded by one of the many delightful casual encounters I’ve had here. I poked my head into the Catholic church to see the exquisite stained glass windows and met two Irish women who took me to the village craft market and invited me on a bird watching festival in a fortnight. They’d never heard of improvisation (well, not in my terms anyway) so we talked about that and about their pursuits: one is a glass artist (as is her mother) and the other is preparing a speech for toastmasters/mistresses on “vocalisations”. She is using bird calls as examples. I might never meet these women again…the opportunities for random conversations seem endlessly possible and enjoyable.

I experienced random notes and chatter in unusual circumstances the night before last. I slept on the floor of the gallery at BCA with 40 others, on inflatable mattresses, to listen to electronic music. Steven Stapleton, a big name in industrial music, musique concrete, drone and other related genres, lives in the Burren. Fans, mostly men, came from Belgium, the UK and many places in Ireland just for the gig. The invitation to host one of his sleep concerts was an extension of his first solo exhibition of collages and paintings now on at the gallery. I booked in, expecting to be evacuating early but I slept for probably 5 hours in the soundscape that Steven manipulated on his turntables, all night. Pulsing drones (like heart beats) formed the base of the work and the cross currents included distance speech and synthesised sounds from mixed environments. I was enthralled with the sonorities and impressed that a sound artist can still be luring the faithful after 30 years. The coffee afterwards was good too.

Stained glass Ballyvaughan Catholic Church

The local pub: opens at 8 every night of the year. A place for conversations