Gort County Galway, 14 September 23

Times like these: the gift of a cabin in the woods near the Slieve Aughty Mountains, County Galway; long days without interruptions; trees, silence, stillness, enough to eat and sleep; the surprise of three deer and a bird singing on the doorstep; creative solitude.

I drove through central Ireland a few days ago: from County Derry, Northern Ireland – where I’d been staying on a farm with my very generous, kind relatives – to the edge of the Burren, south Galway, in the Republic. The island of Ireland might be small but slowing for hay-machinery, speed humps, towns and villages, and taking detours accidently, set me on a slow course: about six hours to my destination. Approaching Cavan from Monaghan the road criss-crossed borders several times as if confused: yellow dotted lines define the edges of the road in the Republic; a continuous white line in Northern Ireland. Metaphors, comparisons, history, maps: plenty of scope for speculation.

Even though the rain and mist obscured the limestone hills on my way here, I am relieved to be back in the South, in the Burren. I’ve spent more time in this part of Ireland than elsewhere and felt almost a sense of coming home. The rock walls, instead of green verges and hedges, remind me to stay very alert on the roads unless I want a grey stripe on the hire car.

But my visit to Belfast in the North hovers, days after taking leave: graffitied walls, the peace wall (an attempt at the ‘bigger picture’); razor wire and tall fences; bunting and flags dedicated to identification; dirty streets and curfew gates; groups of men in dark suits standing on corners; the hop-on-hop-off bus tour selling the Troubles history as if it’s all over and rosy now; the iceberg-resembling mausoleum of the Titanic Museum that draws more crowds than anything else in the North (along with Game of Thrones iconography); very good Indian food; the plethora of languages in the International Youth Hostel; the woman I met from Georgia while strolling through Queen’s University: she was ‘chilling’ after giving a paper on economics at the European Studies conference (UACES), ironically in Belfast, post Brexit. And the welcoming Crescent Arts Centre, a free-thinking sanctuary for artists and writers. While I sat writing in the Crescent café the man near me sketched a miniature landscape from a photograph for two hours without any movement other than his hand. That’s focus.

Before leaving the city I met with an old school friend who has lived in Belfast for more than forty years – through the Troubles – and seen his share of division and explosions and the slow transformation towards peace. “It’s the young people who will change it,” he told me. “They don’t have our memories.” I wonder will he be right. Hate and bigotry is contagious, but so too is harmony.

We had an unplanned walk around Belfast’s back streets after coffee when neither of us could remember where he had parked the car. We found it eventually but not before images of tow-aways and Troubles narratives began to infest my mind, and I could guarantee his blood pressure was unstable until that blue shape manifested.

We drove along the Ravenshill Road to the hire car company, past the Free Presbyterian Church started by Rev Ian Paisley, the man who could have fought for peace and saved hundreds of lives but instead stirred division until he agreed to work (briefly) alongside his greatest rival, Sinn Fein leader Martin McGuiness, as late as 2007. (The Easter Peace Agreement was in 1998). Now they are both dead, and Stormont, the Northern Ireland Parliament, is ‘on leave’ because the DUP (Paisley’s party) has refuse to work with Sinn Fein: power sharing collapsed in 2017. Fortunately there’s another non-aligned party, The Alliance Party, emerging.

Has the window for peace cracked again? Add the contentious Brexit protocol on trade and the recent law passed by the UK Tory government making it almost impossible for Troubles perpetrators of violence (including British soldiers) to be located and charged and the Northern Ireland script stays noir.

I stare past the ferns, trees, ivy and grasses. The three deer that came into focus leapt away when I stood to take a photograph. There’s not a whisper of wind. The sky is bland: I’m guessing more rain is coming. There’s only myself, my mind and some potential for a flowing of imagination.

The haven in the woods

Ballentoy Bay, Giant Causeway Coast, Counties Antrim//Derry, Northern Ireland.

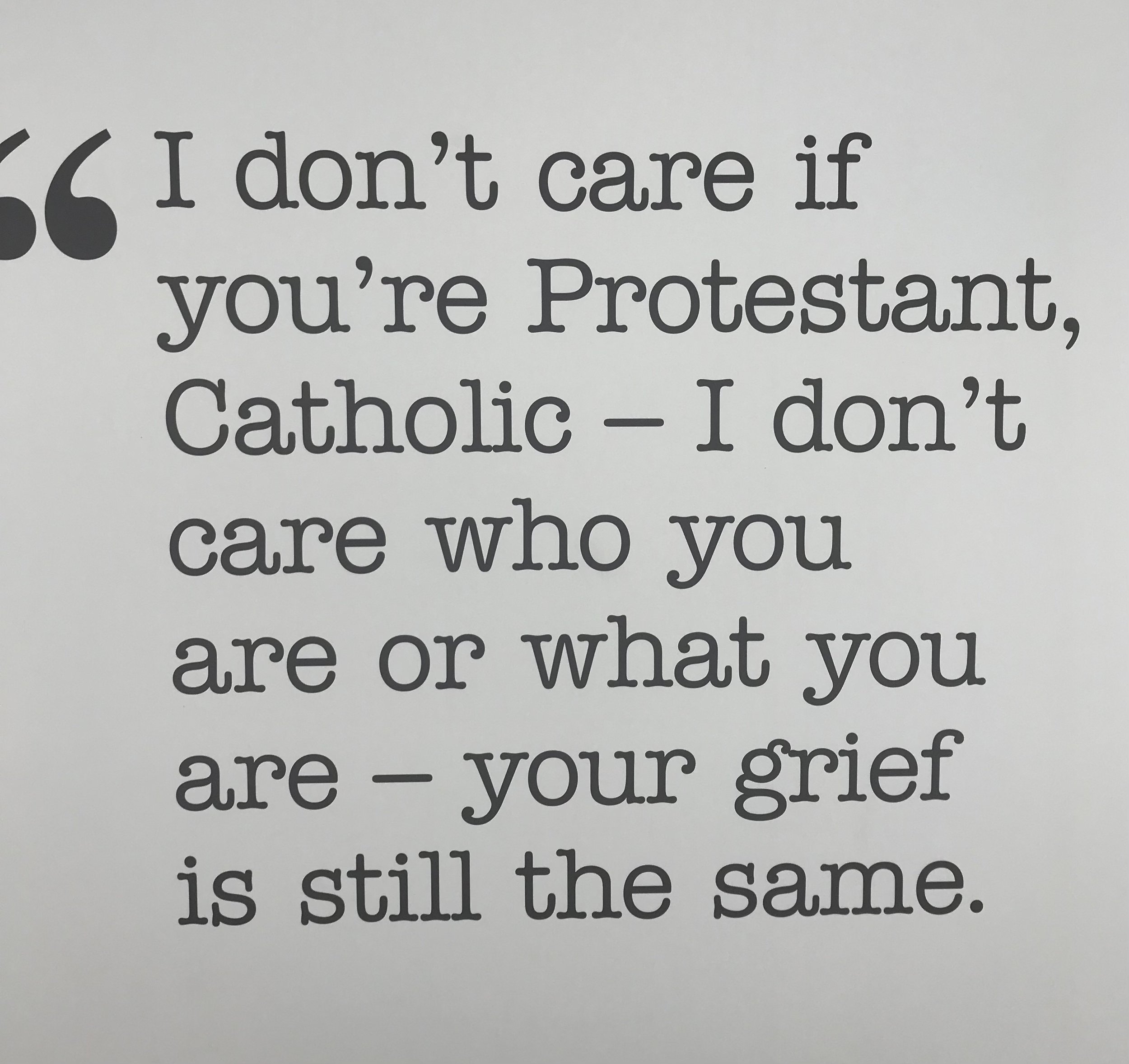

A script on the wall in the ‘Reflection Room’, Belfast Town Hall.